About This Title

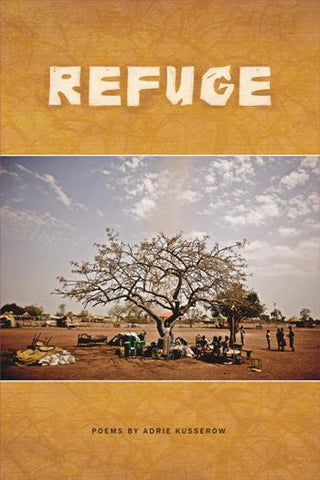

As an anthropologist, Adrie Kusserow’s ethnographic poetry probes culture and globalization with poems about Sudanese refugees based in Uganda, Sudan, and the United States, especially the “Lost Boys of Sudan.” The poet struggles with how to respond to suffering, poverty, displacement, and the brutal aspects of war. Much of this exploration is based in poems in which a mother is also bringing her family to a larger global arena.

“Lost Boy”

For Gabriel Panther Ayuen

Panther sits inside his apartment,

heat cranked up to 80, curtains closed,

a pile of chicken boiling on the stove,

slides another Kung Fu movie into the VCR,

settles back into the smelly,

swaybacked couch, a Budweiser between his legs.

He giggles.

In half an hour he’ll ride his bike

to Walmart, round stray shopping carts

from the cracked gray lot,

crashing them back into their steel corrals.

At first they dropped by all the time,

the church ladies, the anthropologists,

the students, the local reporter.

They all left elated, having found something real,

like yoga and organic food.

The first Thanksgiving, three families booked him.

Leaning hungrily across

the long white table,

they nibbled at his stories,

his lean noble life.

Over and over he told them about lions,

crocodiles, eating mud and urine.

He remembers joining

a black river of boys,

their edges swelling and thinning

as they wound their way

over the tight-lipped soil, sun stuck to their backs.

He remembers dust mushrooming up

around a sack of cornmeal as it thudded

and slumped over, like a fat woman crying in the sand.

And the Americans came alive, with a sad,

compassionate glow, a kind of sunset inside them.

When he got off the plane

the church ladies took him to a store,

bought him fresh sneakers

soft and white as wedding cake.

The next day he walked through whole aisles of dog food.

Two years later, November again,

he’s dropped out of high school—

he can’t take

the kids staring, the tiny numbers and letters

he can’t keep straight,

the basketball team he didn’t make

despite his famous height.

Now he looks like a too-tall gangster,

all gold-chained and baggy-trousered.

The church ladies give him hushed looks:

we regret to inform you, the path you’ve taken is not what we had hoped for.

He’s channel-surfing,

listening to Bob Marley on his Walkman,

his long legs awkwardly pushed out

to each side, the way giraffes

split their stilts

to drink water.

Africa’s moved inside him now,

all cramped and bored, sleeping a lot.

He cracks another beer

starts to float,

the reggae flooding the vast blue-black continent

of his body draped like a panther

over the sides of the sofa.

His cousin calls, she needs more money,

her son has malaria. She can’t afford school fees anymore.

His uncle gets on the phone to remind him to study hard,

come back and build a new Sudan.

Later he stumbles into the bathroom

to brush his teeth, inside him

groggy Africa flinches at the neon light,

paces, then settles in the corner

of its den, paws pushing into the walls

of his ribs with a dull pain.

The next morning he wakes,

stubborn Africa still shoved up against his ribs,

refusing to roll over, into the middle

of himself where he can’t feel it anymore,

into some open place

where he ends

and America finally begins.

Praise for Refuge

“The poems in Adrie Kusserow’s Refuge are dispatches from the world we live in but don’t often, if ever, have to think about. As I write this, Kusserow has stamped her passport to South Sudan, rolled up her sleeves, and continued her ongoing work in the larger world. Not only do the poems in Refuge serve to witness that which would otherwise be given to the erasures of history, they transcend borders and serve as bridges to a deeply human experience.”—Brian Turner

“Whether we like to name them or not, there are responsibilities that the poet must be held to by her readers, and by the ancient chain of voices she makes claim to with the publication of a collection of poetry. Those responsibilities have to do with form, which means an understanding that prosody means a range of musical options, with language, that is, with a regard for words that allows the poet to make us see the world not in a new way, but as it always has been, right before our eyes, and with a keen regard for subject, in this case, one that is unhesitatingly autobiographical, and illustrative of a life interwoven with motherhood, and with an abiding commitment to critical development work in South Sudan. These are not two contrasting subjects someone chooses as ones vocation, but rather that one is chosen by, or better said, that Adrie Kusserow is possessed by, so that the best of these poems emerge from a need to have been written. They are bold and new and original in their emotional and geographic sweep of the human landscape. They are beautiful to feel on your mouth when you say them out loud.”—Bruce Weigl

“Kusserow's splendid verses bring us devastatingly close to the recent horrors of the southern Sudan and its lost boys. Her ethnographic gaze is compelling and her poems plunge us into unfamiliar social worlds, bringing us the news we need to know. Both anthropology and poetry stand enriched by her work.”—Renato Rosaldo, author of Culture & Truth

About the Author

Adrie Kusserow is Professor of Cultural Anthropology at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, VT. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from Harvard University and an M.A. in Comparative Religion from Harvard Divinity School. Her first poetry collection Hunting Down the Monk was published by BOA Editions in 2002 and carried a Foreword by Karen Swenson. Her most recent international fieldwork trips support girls’ education (South Sudan – www.Africaeli.org) and Youth Media Literacy and Gross National Happiness in Bhutan. She lives with her family in Underhill Center, Vermont, where she was born and raised.

Publication Date: May 7, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-938160-08-0

© BOA Editions, Ltd. 2013